Following my last article on the recently passed Herbie Flowers, it felt fitting to return to some of the behind-the-scenes musicians in the next instalment of my (ever-so-intermittent) Great Guitarists series. I have already shone a light on some of my personal favourites, including Steve Cropper and Barney Kessel, and this time I’m focusing on another sideman who played on so many sessions he had the nickname “Mr 2500”, Cornell Dupree (1942-2011).

There’s not many guitarists, even in the session world, whose credits include such a diverse range of artists, from Barbara Streisand and Mariah Carey to jazzers Herbie Mann and Sonny Stitt, as well as rockers Joe Cocker and Ian Hunter.

Born Cornell Luther Dupree Jr in Fort Worth, Texas. His career began in Texas, having decided to learn guitar after seeing Jonny ‘Guitar’ Watson in concert. While playing in local bands, he will have undoubtedly encountered and opened shows for other well-known and respected Texan artists such as T-Bone Walker, Lowell Fulson, Albert Collins, Lightning Hopkins, as well as country stars such as Roger Miller and Ray Price.

In the early 1960s, Dupree was called to New York by saxophone player King Curtis (whom he had known from their days in Fort Worth) to join him in his band The Kingpins. This group were a joined a few years later by a second guitarist – a certain James Marshall Hendrix…

In a band without a keys player the two guitarists worked together to fill out the band’s sound; Hendrix quickly taking on soloing duties while Dupree filled out the rhythm section. While Hendrix was dismissed from the band in 1965 (for being too loud, too flashy and often late to gigs), Dupree stayed with King Curtis, both onstage and in the studio, up until the band leader’s death in 1971.

Dupree made is first foray into session work in the mid-sixties, while still in the Kingpins. He spent much of the next decade and a half as a much called upon ember for Atlantic Records’ in-house studio band. In the the 1970s alone, his playing graces the albums of artists such as Aretha Franklin, Grover Washington Jr., Donny Hathaway, Miles Davis, Lulu, Herbie Mann, B.B. King, Freddie King, Billy Cobham, Paul Simon and many, many more.

Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler stated (in the liner notes to Dupree’s 1994 solo record Bop’n’Blues) that Dupree’s ability to play lead and rhythm at the same time meant that only one guitarist was required to provide what was needed. Thanks to recommendations from former bandmates such as bassist Chuck Rainey, Dupree soon gained a reputation as the only guitarist a producer might need.

Amongst all this, Dupree not only found time to release over a dozen solo records, but also founded the jazz fusion group Stuff. Stuff were a who’s who of session musicians including bassist Gordon Edwards, Richard Tee on keys and Steve Gadd on drums and fellow session guitarist Eric Gale. Their appearance at the 1976 Montreux Jazz Festival is available as a concert video and LP (see one of the tunes, Stuff’s Stuff, below), showcasing these players at the top of their game.

In later years, Dupree continued to perform despite declining health. He can be seen at the end of the Bill Wither documentary Still Bill playing ‘Grandma’s Hands’ with Withers while using an oxygen tank to aid his breathing. He died in 2011 while waiting for a lung transplant as a result of emphysema.

Playing style

As a soul-based guitar player, much of Dupree’s playing used a clean sound with minimal effects, except for a touch of reverb, in most cases. This allows his playing to shine through without becoming overly dominant in the mix. His style demonstrates that blues and gospel-based pattern of question & answer, where one melodic phase acts as a short opening statement (of less than a bar in length), before being ‘replied to’ by another phrase of similar length.

His choral work makes use of the sort of flickering embellishments familiar to use through Jimi Hendrix making extensive use of them (along with Curtis Mayfield and others). In Dupree’s case, they always feel very tastefully executed, and seem to leave ample space for the artist (usually a vocalist) whom he is backing. In this sense, he is following the golden rule of the sideman: to make the featured artist sound good.

An integral part of Dupree’s lead guitar style is his use of sliding sixth to augment and enhance the chords he was soloing over. For those who are unsure about sixths, you can find my explainer on sixths and similar intervals here. Steve Cropper was a big proponent of this technique, and like Dupree, one of the guitarists I kept hearing on soul records time and again, without really knowing who these backing musicians were until I was older and starting to dig deeper into this side of my own guitar playing.

Equipment

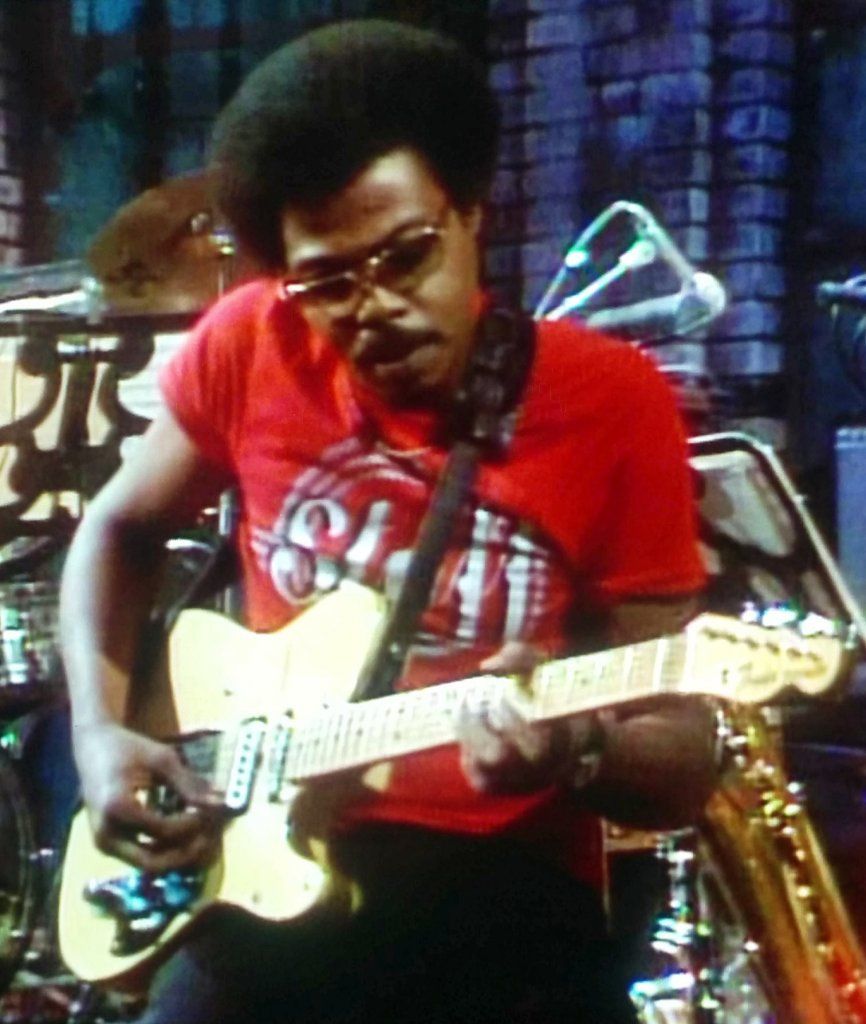

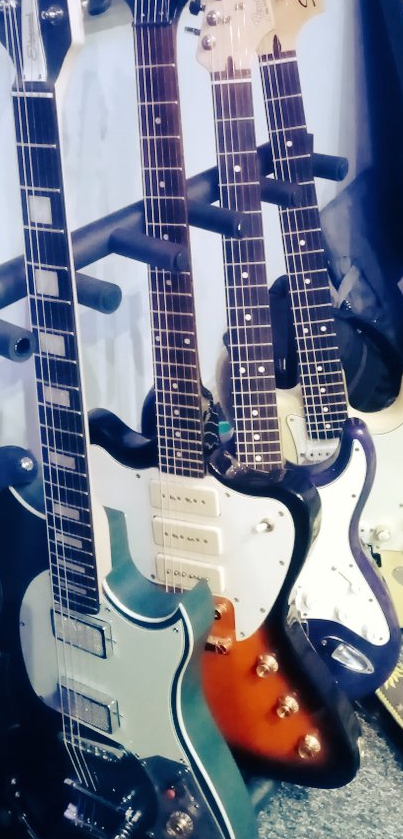

Although reported to have started out on a Les Paul, then a Les Paul TV Special (a stripped down, P90-equipped version of the Les Paul), Dupree appears to be mainly pictured with a modified telecaster (another common element he shares with Cropper). He is often shown in older pictures with a white/faded blonde model, with a third DeArmond style pickup added in the middle position. This addition meant the pickguard could not be refitted onto the guitar, so Dupree appears to have filled in the screw holes with rivets. It certainly makes for a distinctive look!

In 2002, Yamaha made a Cornell Dupree artist model Pacifica, using their telecaster-style ash body with a one piece bolt-on maple neck. This signature model had the same atypical pickup configuration that Dupree had been using for decades on his modded Telecaster. The Pacifica came with a neck humbucker and Seymour Duncan ‘Hot Rails’ in the bridge position, controlled by a three-way switch to toggle between them, but not a rivet to be seen!

There was also an alnico V single coil in the middle, which could be added to any selection via it’s dedicated on/off switch. I’ve seen this mod on the guitars of a few professionals, particularly those who like to get the most sounds out of just one guitar (something I have written about before). Indeed, I’ve modded a few of my own guitars to ensure a similar level of flexibility and range of sounds (read about some of my mods here).

What can Cornell Dupree teach us?

Dupree was the master of economy of style, never overplaying. I guess that’s one of the reasons he was always asked back to more sessions; he knew how to serve the song. Another factor is his clear professionalism. As with Herbie Flowers, showing up, acting professional, and learning to anticipate the producers needs is a key element to a successful career as a session player.

While his former bandmate Hendrix might be more recognisable, having made a wonderful career on his own terms (and in his own time, it seems), Dupree seemed content to remain slightly off-centre stage. As a result, he had a long and varied career. Indeed, although Hendrix is undoubtedly the more seen, I’d argue that Dupree – thanks to his appearances on thousands of recordings by some of the music’s biggest-selling artists – may actually be the more heard of the two. In my mind, that’s quite the achievement.

You must be logged in to post a comment.