It’s hard to believe that we’re in the final three months of the year. What a year it’s been! I’m sure no one could have reliably predicted the majority of changes which most of us have had to undergo, hopefully on a temporary basis, because of this pandemic. I hoped that it might offer more time to get through my oft-mentioned (and ever increasing) ‘to read’ pile. However, if 2020 has taught us anything, it’s that life doesn’t always go the way you expect it to.

Still, there has been some reading since the last installment (which you can read about here), and here is a brief review of it…

The Italians by John Hooper (2015, Penguin)

An affectionate and sometimes amusing look at the characteristics common to Italians, and why that might be the case. Hooper also reiterates that Italy is a relatively new country (as a unified whole), and spends almost as much time highlighting what separates Italians from different regions; north and south; Romans and Sicilians; mountain dwellers and those who reside by the country’s ample coastline, and so on. Hooper regularly interjects anecdotes from his extensive time living and working in Italy as a journalist. These passages give the book a greater cohesion, in that the presumed reader (and Englishman) sees the situations unfold through the eyes of the author, and with similar inherent sensibilities. However, Hooper restrains himself from writing this as a straightforward memoir, which I expect that has increased it’s potential readership.

I read this book during lockdown in England. Of course, Italy had imposed one of the most stringent lockdowns of any country in the world, and the Italians have seemingly been obedient and compliant. This seemed to go against one of the common reoccurring themes in Hooper’s observations; that Italians will regularly bend the rules to suit their needs or preferences. The reports I was hearing on the news in 2020 didn’t sit with this assessment, until I considered another of the books themes – the emphasis and commitment Italians place on family. From this angle, undertaking the strictest measures, which seemed like virtual home arrest to some, made sense, as it gave your elderly relatives a fighting chance of making it through this madness alive. And that, argues Hooper five years before any of this was upon us, is a key characteristic of Italians. Recommended for anyone with an interest in staying in Italy for longer than an average-length holiday.

The Finkler Question by Howard Jacobson (2010, Bloomsbury)

Jacobson’s 2010 comic novel about three male friends – two of them Jewish and a third man who suddenly feels that he might be, won the Booker Prize for Fiction in 2010. This sudden interest in the religion of his friends is the author’s way of examining the universal themes of life and society. It is amusing in places, and the characters are interesting and well-written. Yet I certainly wasn’t gripped by it as much as I had been led to believe the reviewers who had gushed over this novel upon it’s release. Humorous and touching, yes, but also confused in places, and ultimately, slightly underwhelming.

Athelstan by Tom Holland (2016, Penguin)

A recent addition to the Penguin Monarchs series (that is, books on British monarchs published by Penguin books, although there’s a pun about Emporer Penguins in there somewhere), this book examines one of the lesser-known pre-1066 Kings (who wasn’t Alfred the Great).

I enjoy Holland’s writing, having read several of his books previously – in particular, I thoroughly recommend Rubicon, about the last gasp of the Roman Republic. At 160 pages, this is a quick read, but it covers what is known about Athelstan, from the few sources available. Personally, I’m pleased that Holland resisted the temptation to pad the book out with unnecessary additional information or unfounded presumptions.

Utopia for realists by Rutger Bregman (2016, Bloomsbury)

Alternate subtitles for this book, depending on country of publication, include and how we can get there (UK) and the slightly less pithy sounding the case for a universal basic income, open borders, and a 15-hour workweek (Holland). Although the latter of these two subtitles is somewhat unwieldly, it must be said that it up this book’s subject matter much more effectively. The book originated as a series of articles for the Dutch online news site De Correspondent by Bregman, a popular historian, and was later complied and translated. It has quickly became a bestseller, which ringing endorsements from a wide range of economists and politicians across the world.

The text centres on the three polices highlighted in the original subtitle, along with the principle that ideas can change the world, according to Bregman, who states “people are the motors of history and ideas the motors of people”. Of course, there are many who have said that Bergman strays into idealism, and it will certainly prove more popular with readers of a more left-leaning political persuasion. But Bergman is only aiming to issue a challenge, or a promise, of what could be possible but I doubt if the title Utopia for Idealists would have sold quite as well. A manifesto for a brighter future? Maybe not by itself, but a good place to start.

Goshawk Squadron by Derek Robinson (1971, Cassell)

In the afterword section of the book, Robinson recounts his inspiration for writing the story. He read a former R.A.F. pilot describe the tactic of the world’s first fighter pilots during WWI as “to sneak in unobserved behind his opponent and then shoot him in the back”. Hardly the cavaliers of the clouds they have often been immortalized as in tales such as the Biggles series, amongst many others.

This Booker Prize shortlisted book paints it’s fictitious characters in a more truthful light, based on the diaries and letters of real WWI pilots. The book was met with anger from veterans of the Royal Flying Corps (the forerunner to the Royal Air Force) when it was first released, but reading it in 2020, it feels much less controversial now – the idea of a ‘lovely war’ has remained a 20th century concept – but the story is no less gripping for that fact. At just over two hundred pages, it’s a relatively fast read, but I found that the story stayed with me long after I had replaced the book on the shelf.

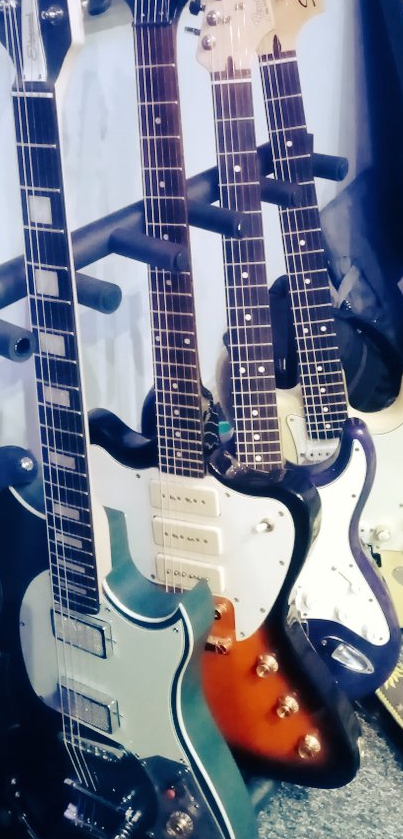

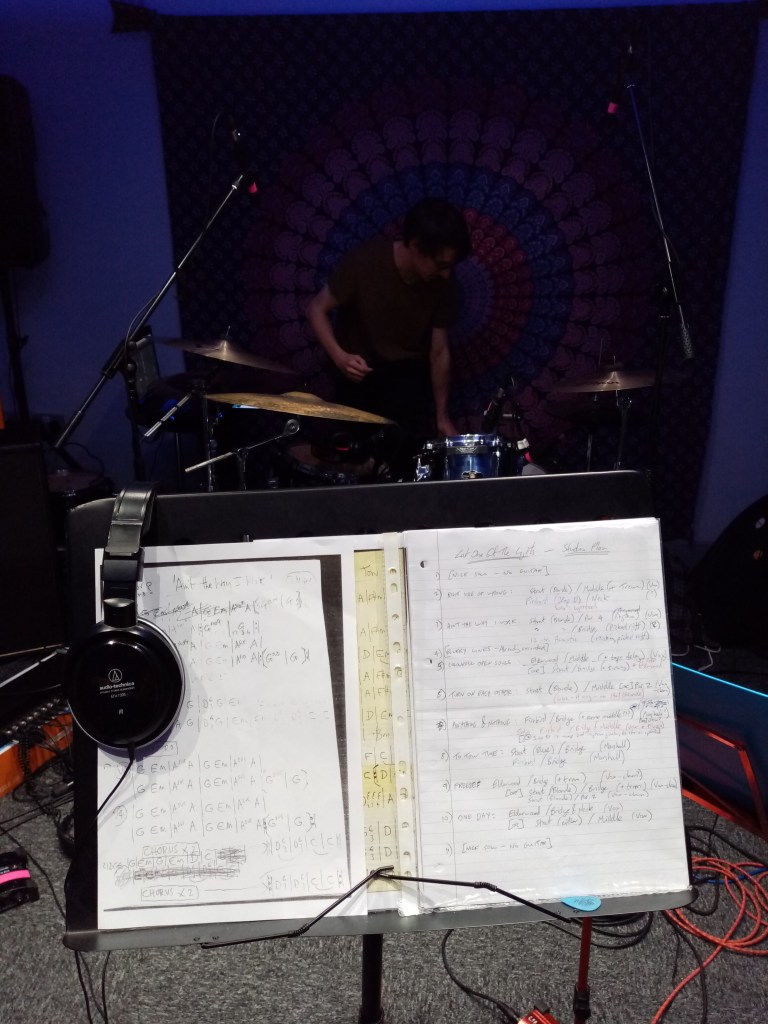

The next and final installment of this series (due in late December) will feature two novels I have been looking forward to reading. You can also expect updates on some upcoming studio dates and an in-depth review of a new guitar built for me recently. Until next time…

You must be logged in to post a comment.