Is tone more important than technique? That’s a great debate to have, but not today…

Yet when most people listen to music, it is the tone of an instrument such as a guitar which catches and holds our attention first, so tone is pretty important. But how do we improve our tone? To do this, we need to understand what makes the tone we hear when we play guitar.

In this article, I will list the various various factors that impact the tone of your instrument, starting from the last one in the chain before the sound reaches our ears, all the way back to where the notes come from…

Amplification

As the last step in the signal chain, the sounds that come out of your amplifier (or PA speaker if you’re using an amp simulator, etc) if what you and the audience hear. Everything that comes before this will be coloured by the natural sound of the speaker, it’s valves/circuitry and whatever tones you dial in.

It’s so common to see guitar players spending most of their money on a guitar, while skimping on amplification. While it’s certainly true that it’s a good idea to have the best equipment you can afford, that super-expensive Deluxe Strat would actually sound too different to the Squier Bullet Strat if you’re playing them through the same amp.

A good amp can adapt your sound. Weaker, thinner-sounding pickups (such as single coils) can be ‘beefed up’, while humbuckers with too much push can be fixed with a mid-range cut. And that’s before we look at overdrive, distinction, reverb and effects such as chorus, flange, phaser, etc, all of which further colour the natural tone of the guitar. There is dangers here, too. Overuse of EQ or effects can lead to something which sounds over-processed, or just plain bad (think of the infamous ‘wasp in a jam jar’ sound attained from too much fuzz and treble).

Luckily, the market is full of affordable amplification options. There are also various digital modelling amps and units that can recreate the classic tones of famous (and incredibly expensive) vintage and boutique amps. To have so many genuinely realistic sounds available in one place, at an affordable price, is a relatively new luxury that all guitarists should be taking advantage of.

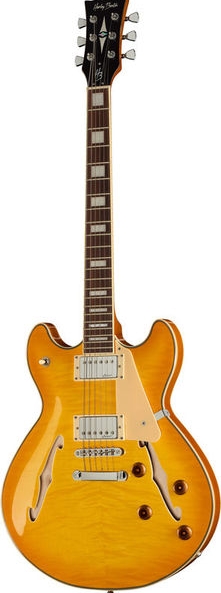

Pickups

After amplification, the second most crucial factor affecting the sound of an electric guitar is the pickups. These devices, magnets wrapped in wire, convert the vibration of the guitar’s strings into an electrical signal to send onwards in the chain.

I have spoken in earlier posts about the differences in pickup type and how some may be more versatile than others (see the articles in question here and here), but to sum up, keep in mind these basic points:

– The lower the output of a pickup is, the cleaner it will sound as you increase volume

– Humbuckers can handle higher-gain settings with much less extraneous noise (hence the name, a reference to their hum-cancelling qualities)

– Different types of pickups will naturally sound different (i.e., those made with individual magnet ‘slugs’ for each string, as opposed to ceramic bars which run the length of the pickup); do plenty of research before you commit to buying!

Volume

As hinted at above, some pickups will retain their ‘natural’ tone more easily than others, depending on their strength. However, in many cases, judicious use of the volume control(s) on your guitar can help find the sweet spot in terms of sound. Unless there is a treble-bleed circuit installed within the circuitry of your guitar, most pickups lose a little top end as the volume is turned down. I find that rolling back the master volume on my Strats to around 7 or 8 takes out some of the harsher treble frequencies for a nicer, more rounded-out sound. It also leaves a little headroom to boost your volume and cut-through for lead lines.

Similarly, turning down the gain on the front end of an amp or overdrive pedal can allow for a cleaner sounding boost instead. On a pedal like a Tubescreamer (or the many brilliant clones available), turning down the gain allows you to use the volume to amplify the tone of your guitar/pickups without colouring it too much – and a cleaner sound usually cuts through more effectively than drenching your tone in distortion. Listen to those classic Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple records, and notice how there is surprisingly little distortion on the guitar most of the time. The power comes from the volume.

Strings

We’ve now reached one of the cheapest things which affects the sound of your guitar: strings.

Generally speaking, most people experiment with different thicknesses and brands when starting out as a guitarist, eventually settling on the ones which feel most comfortable under their fingers and break as infrequently as possible. But not all strings are alike. Their material (usually a type of metal or alloy) and various coatings have an effect on how the string vibrates, and therefore how it transfers sound to the pickups. Also, a strings that feel different will result in us adjusting the way we play, perhaps without meaning to.

Many guitarists used to believe that thicker strings meant more tone. Think of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s gauge 13 strings and the huge bluesy tone he achieved. Yet also bear in mind that the Texan guitarist used heavy strings because he had large hands and and had developed a heavy-handed playing style; he used thicker strings to try and keep them from snapping all the time (and there’s lots of evidence from live footage of his performances to suggest he wasn’t entirely successful in this aim). Foe a while, I had one of my Strats set up with gauge 11 strings and down-tuned a half-step to Eb (as I have been told the late, great Jeff Beck used to do). This was largely a practical setup for the band I was working with at the time, but any guitar players believe doing this allowed the thicker strings to vibrate a little more ‘loosely’, which led to an improvement in tone. I can’t say I noticed much of a difference in the heat of a live show.

As a counter argument, B.B. King and Billy Gibbons used gauge 8 strings, and still managed to achieve great sounds from their instruments. For Gibbons, this may have been down to the famous ‘pearly gates’ humbuckers on his Les Paul, as well as his amplifier tone. As for the King of the Blues…

Fingers (and picks)

B.B. King would have sounded like B.B. King on any guitar. Indeed, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page did always manage to sound uniquely like themselves on any guitar they played. The same can be said of virtually any famous guitarist you can think of, and indeed the rest of us. Why? Fingers.

The most overlooked area affecting the tone of your guitar (and following the rough cost-order of this list, the cheapest!) is the parts of your hands which make contact with the strings and create the sounds in the first place. This goes for either hand, but the fretting hand is the one which is holding the strings and notes in place.

Obviously, there can be a huge difference between picking with your fingers or using a plectrum, and the type of material you use for picks should be taken into account and experimented with until you find what works best for you. However, for your fretting hand, there’s not much we can do to change how this affects the sound overall. The good news is, that’s okay! You have been using the same hands since first picking up the instrument and your sound will always take this into account, if you didn’t realise you were doing it. Embrace who you are! Also, as your fingers are the first stage in the ‘sound chain’, there’s plenty of ways to change the sound as we go through pickups, effects, amps, etc… Take some time to explore the huge range of options and see what works for you!

Final thoughts

From all of the elements described above, which one would I single out as the most useful for tone shaping? That’s a tough call, and ultimately a very subjective topic. However, for me, I think volume is the most underrated element in the signal chain, and one I’ve taken years to master in terms of my own guitar sound and playing.

In my early days of playing guitar, I sometimes strove to change the sound of my guitar tone, frustrated that I could only go so far without seriously reprocessing the sound into something which might end up sounding synthetic. Yet as I performed live more often, I noticed that out of all of the comments people would make to me about my playing, tone was only ever mentioned in a positive light (the same could not be said for technique, unfortunately). Records capture faithful reproductions of the sounds I started with when tracking them. No one has ever said I have a bad tone. The only person who (sometimes) wanted to change it was me.

Maybe guitar players worry about this too much? Maybe we’ve been conditioned to overthink our tone because it serves the interests of the musical instrument industry? Thousands of companies, from instrument makers to amplifier manufactures, and creators of effects or inventors of accessories, rely on our need for more gear, to finally find that one product that will fix the problem in our sound. But it rarely does. Luckily, there’s always another thing to buy…

I’m sometimes prone to this line of thinking too. That’s the side-effect of living in a capitalist economy, I suppose. I’s never been easier to get purchase anything we need, but we have to be careful not to lose ourselves in the process, and hold on to the simple joy of music-making which got us started in the first place. I came to be happy with the sounds I produce from my fingers. I think it’s had a positive effect on the music I create. It can do the same for you too. Just remember to pay attention to the various stops along your signal chain to ensure everything is working in the best possible way for your sound, and you won’t go far wrong.

You must be logged in to post a comment.