Amongst the most famous blues guitar players, there are the so-called Three Kings of the Blues. All unrelated despite the shared surname, these three guitar players helped to define the sound of modern blues guitar.

We have already looked at Albert King and how his unorthodox technique and biting sound left a huge influence on later guitar megastars such as Jimi Hendrix, Buddy Guy and Stevie Ray Vaughan (to name just three). This time, we will focus on the man who is – quite probably – the most influential blues guitarist of all time: B.B. King.

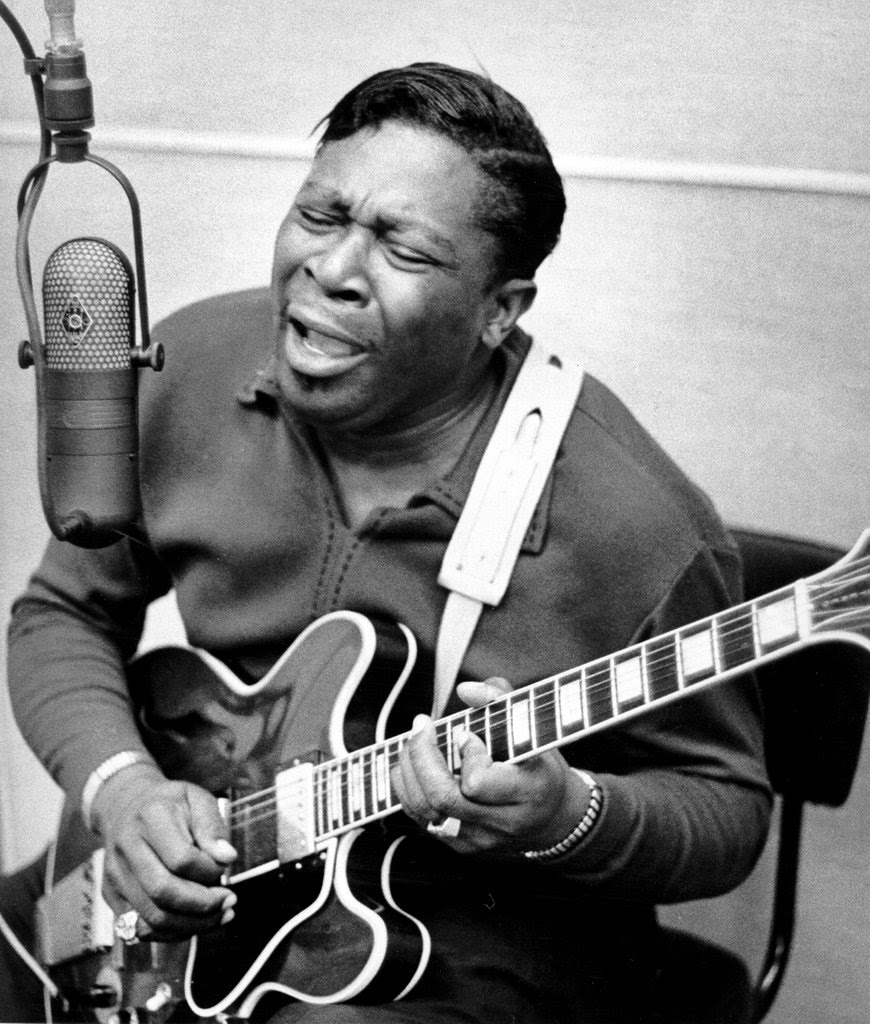

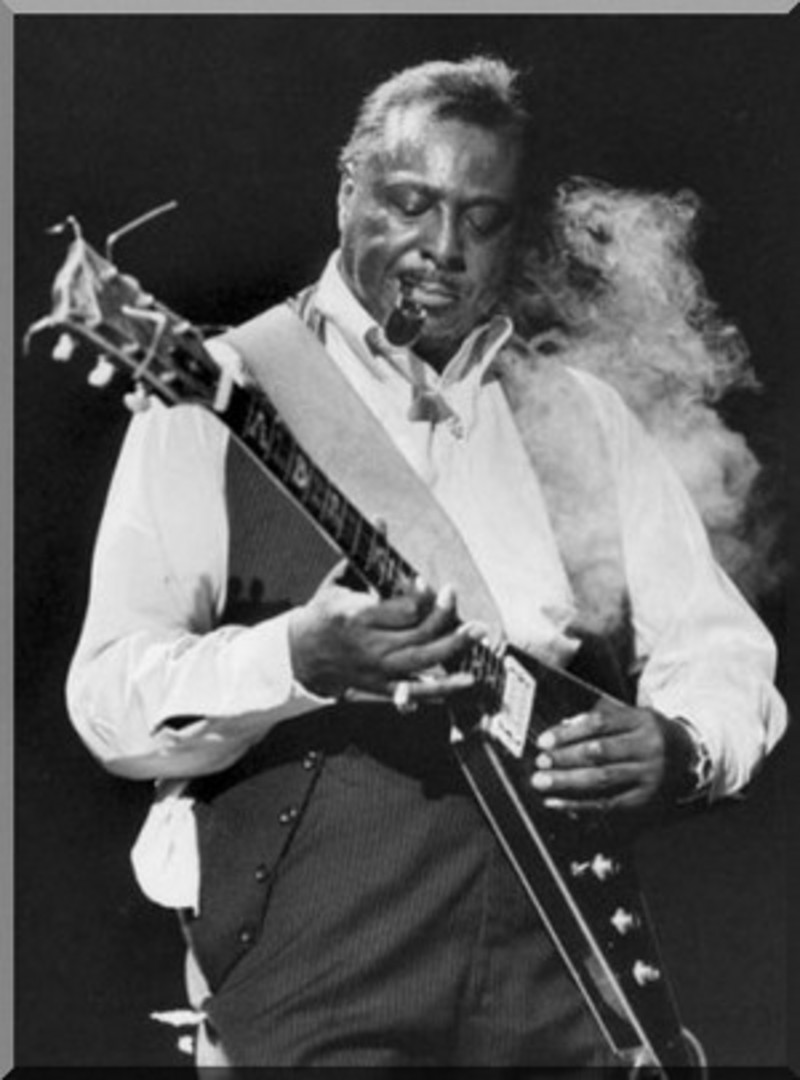

Much of King’s influence is indirect, but the vast majority of guitar superstars in the 1960s and 1970s owe a debt to this man’s melodic and simple, yet incredibly emotional and effective, style of lead guitar playing. He was also a brilliant singer, working in duet with his own guitar playing, like the singer-guitarists of the early blues period, but bringing the genre into the modern electric era with a wonderfully soulful edge.

Early years

Riley B. King was born on the 16th of September, 1925, on a cotton plantation in Leflore County, Mississippi. In his teens, King sang in a local gospel choir and learned his first few guitar chords from the preacher at his church. He spent his late teens working as a tractor driver and as a guitar player for a popular touring choir, performing at religious services across Mississippi. But after hearing Delta Blues on the radio, King aspired to become a radio musician. Following a move to Memphis, King began to realise this dream, performing on various radio shows and eventually landing his own on the station WDIA. Here he soon garnered the nickname “Beale Street Blues Boy”, which was shortened to “Blues Boy”, eventually becoming the “B.B.” he was known by for the rest of his career.

It was during his stint at WDIA that King first met T-Bone Walker, later stating “Once I’d heard him for the first time, I knew I’d have to have [an electric guitar] myself”. Aside from the Delta Blues and T-Bone Walker, King’s early blues influences were singer-guitarists such as Blind Lemmon Jefferson and Leadbelly. He was also influenced by early jazz guitarists Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt.

What these players had in common was a knack for beautiful single-line guitar melodies, and an ability to work with singers and other instrumentalists in a ‘question and answer’ style which King would later perform with himself, singing his songs and responding to his vocal lines with a guitar lick.

Finding success

King became popular on the Beale Street blues scene in Memphis, performing with other well-known acts of the time, such as lifelong friend Bobby Bland. He cut some early records with Sam Phillips, who later founded Sun Records (and discovered Elvis Presley), but these did not chart too well. However, he soon had a number one record on the Billboard Rhythm & Blues chart with 3 O’clock Blues in 1952. This was followed by a run of successful blues singles which helped King become a well-known name on the national blues touring circuit.

During the 1960s, King received the nod of approval from a singer he much admired, Frank Sinatra. Sinatra had arranged for King to play at the main clubs in Las Vegas. King credited Sinatra for opening doors to black entertainers who otherwise were very rarely, if ever, given the chance to play these venues.

Water from the white fountain didn’t taste any better than from the black fountain

BB King, quoted in Esquire, 2006

By the end of the 1960s, groups associated with the so-called British Invasion (see below) allowed King to reach a larger audience than before, through exposure to white audiences. This included opening for The Rolling Stones on their US tour of 1969.

BB King never abandoned the blues. But his biggest breakthrough hit, The Thrill is Gone, released in 1969, showed that the blues could be framed in a more modern, funk & soul-based setting that left room for King’s equally soulful singing and lead guitar voices. Although the song had been written in the early 1959s, King’s rendition, the first time he incorporated strings into his arrangements, earned him a Grammy Award for Best Male R&B Vocal Performance in 1970 and became his signature song.

The 1970s saw King release similarly soul-blues singles such as Hummingbird and I Like to Live the Love. For the latter of these songs, the studio version of which feels like a classic soul record, but here’s a slightly faster version from a concert King gave in Zaire (now known as The Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1974 – look out for legendary session guitarist Larry Carlton on backing guitar:

King’s music included elements of funk, soul, gospel and jazz, all combined to create a unique style which many bluesman continue to emulate to this day. By the 1980s, King was already an Elder Statesman of the blues, and the LPs he released over the decades from here until his passing in 2015 were largely albums of duets, featuring a veritable Who’s Who of stars from the world of the blues and beyond.

Influence

Early on, King transcended his musical shortcomings — an inability to play guitar leads while he sang and a failure to master the use of a bottleneck or slide favored by many of his guitar-playing peers — and created a unique style that made him one of the most respected and influential blues musicians ever.

LA Times obituary of BB King, 2015

Although his urbanisation of the blues brought forth some detractors, King’s economy of style proved influential on many of his peers, not least the generation of guitar players who followed him, such as Buddy Guy. Jimi Hendrix was also a big fan of King, incorporating some of his licks into his eclectic vocabulary of psychedelic blues playing.

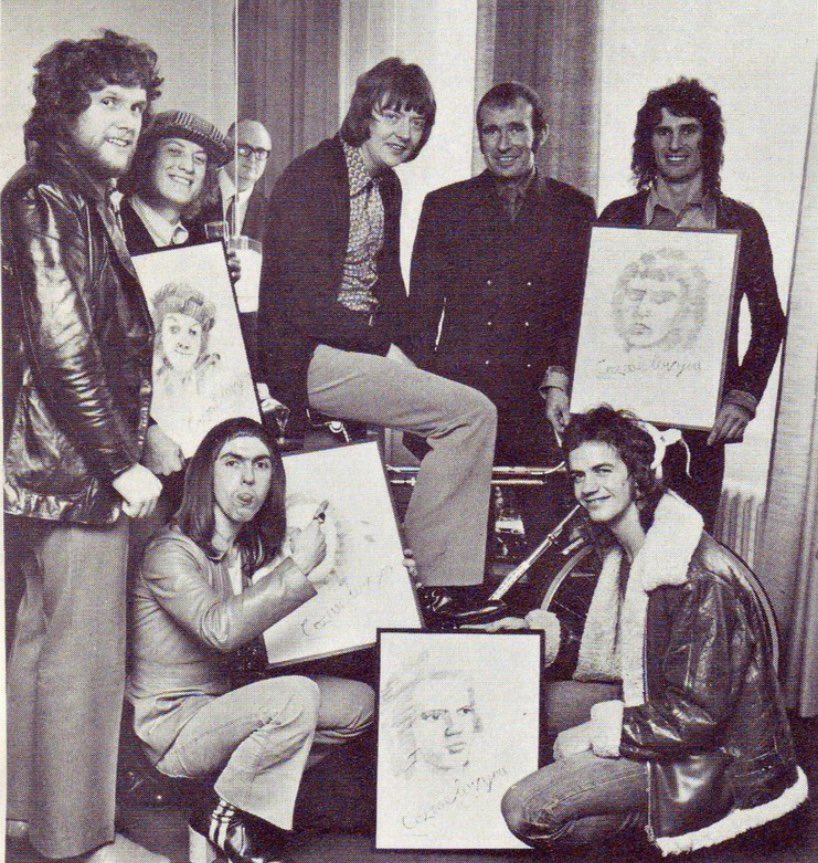

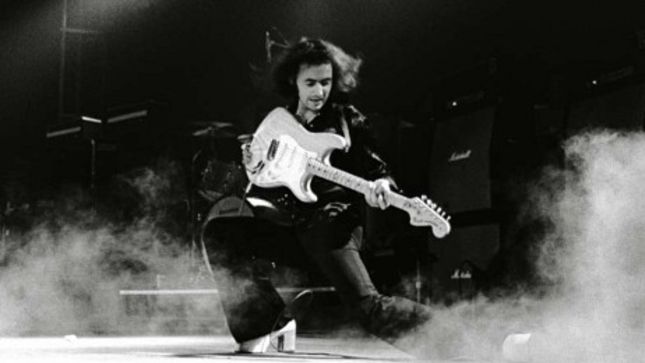

However, King’s greatest influence came from across the pond in the United Kingdom. While blues artists were not getting much airtime on mainstream radio in the US, young guitar players in Blighty were eager to snap up any blues records which came across the Atlantic. The resulting generation of guitarists redefined the sound of the blues, taking their bands back across to the US and finding great success. Groups such as The Rolling Stones (with guitarists Keith Richards, Brian Jones and later, Mick Taylor, who who displayed BB King’s influence the most overtly), The Yardbirds (which featured, at varying times, legendary guitarists Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page) and Fleetwood Mac (Peter Green) were just some of the British bands who followed the success of The Beatles, and helped US audiences rediscover their own elder statesmen of the blues, such as King.

Yet King’s influence didn’t end with the generation which followed. He recorded the rock-based duet When Love Comes To Town with U2 on their 1988 album Rattle and Hum. The arena-filling bluesman of the moment, Joe Bonamassa, puts his success down to a meeting with King when he was just twelve years old, leading the young guitarist to act as an opening act for King, from which he has grown an illustrious career of his own. The groove from King’s 1970 song Chains and Things was a huge inspiration for Gary Clark Jr. The track was also sampled by hip hop artists such as 50 Cent and Ice Cube.

Looking back from the history of guitar, blues or otherwise, from the mid-20th century to date, you’d be hard-pressed to find a guitar player who doesn’t owe King a debt f thanks, be it directly or indirectly. It has even been said that a young Elvis Presley was a fan, long before he helped create a newer, uptempo version of the blues known as Rock’n’Roll…

Equipment

All this passion and soul, not to mention influence, from a disarmingly simple setup. Although early photos sometimes show King playing a Gibson ES-5, most of initial singles with RPM were in fact recorded on a Fender Esquire, the forerunner to the Telecaster.

However, by the 1960s, King had switched to the guitar he is most associated with, the Gibson 335.

The semi-hollow design allowed space for King’s lead lines to ‘sing’ a little.more freely, but in an era of loud onstage volumes, it also meant the guitar was prone to feedback. To counter this, King used to stuff the f-hole with material to cut down on feedback. Eventually, Gibson began making him his own signature model 335 without f-holes. All of these guitars have since been known as Lucille, following an incident where a fire was caused at a show, all started over a woman of the same name.

For amplification, King favoured the sound of a Fender Twin. King has stated his belief that Fender amps were “the best ever made”, in terms of sound and durability.

During the seventies and eighties, King also used a Lab Series L5 2×12″ combo amp. This was probably an upgrade of sorts on the Twin, while still retaining the tone King loved and was renowned for.

Recommended listening

There are plenty of records to choose from, spanning the entirety of King’s long career. You won’t go wrong with any of his releases, but for a taste of his early singles, check out The Modern Recordings: 1950-1951. These tracks (including rare alternate takes of his original 45rpm releases) most strongly showcase the jazzy influence of T-Bone Walker in King’s melodic guitar playing.

In terms of King’s collaboration albums, there’s plenty to choose from. Lucille and Friends (1995), Deuces Wild (1997) and B.B. King & Friends: 80 (2005) feature a wealth of well produced blues duets with the cream of the rock and blues worlds, recovering songs from King’s repertoire. King also recorded albums of Louis Jordan covers, as well as records and live albums with the singer Bobby Bland. However, his 200p release with Eric Clapton, Riding With The King, shows both guitar players on top form.

However, the quintessential B.B. King record, and one that I believe is essential listening for any blues guitarist, is his 1965 release Live At The Regal, a concert recording from a show at The Regal Theatre in Chicago on the 21st of November, 1964. Hailed as one of the greatest blues albums of all time, this record showcases King at his finest, and is one of the records which helped to shape me as a guitarist. Highly recommended.

As always, I’d love to hear your thoughts. King was a prolific live performer, so if you were ever lucky enough to see the master at work onstage, do get in touch to share your experiences. Until next time…

You must be logged in to post a comment.