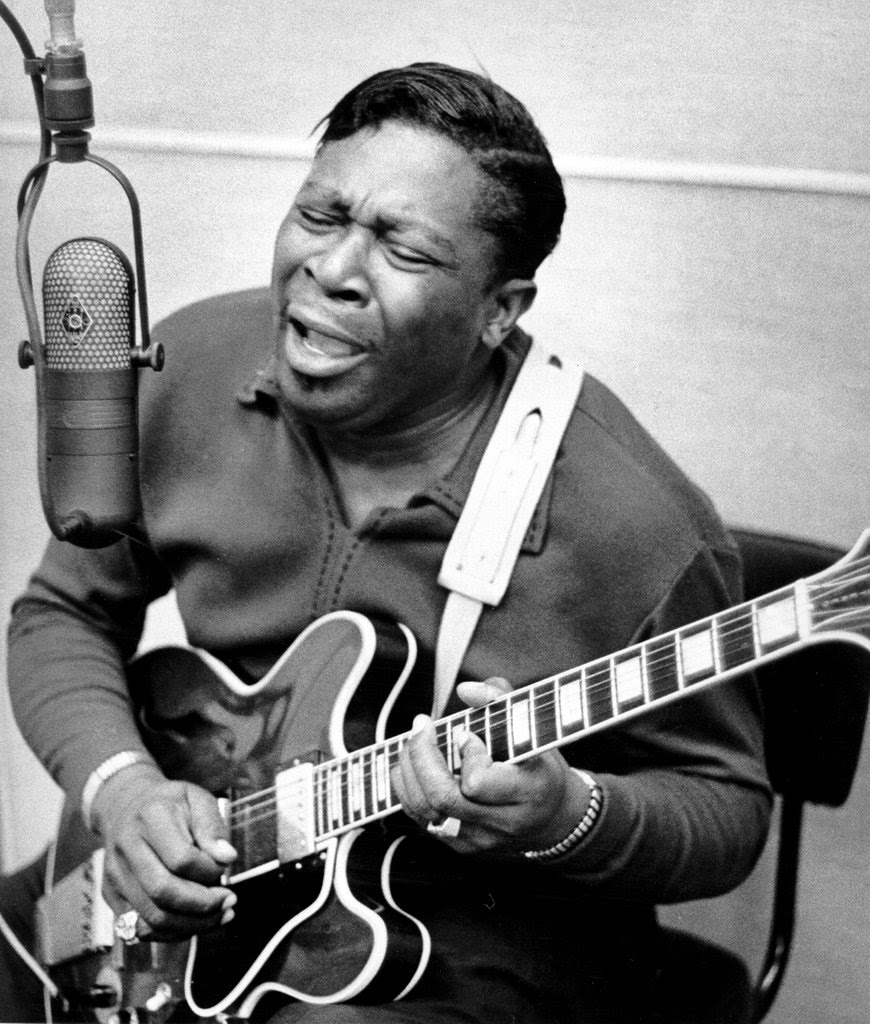

Now more than ever, the world is a busy place. In the age of social media and being reachable in one form or another virtually anywhere in the world, we find our time is filled up with ever-newer demands on our attention. Yet classic musical genres like the Blues remain a steady fixture, especially in the guitar-o-sphere, be it as the rediscovery of BB King and his compatriots by each new generation, or the influence of blues guitar in the apparent resurgence of the guitar solo in modern chart music.

I’ve certainly had a busy summer, although in my case it was a few months full of gigs, including in some new and interesting locations (which I will tell you about in an upcoming post). But now things have settled back into something resembling a normal routine – or as normal as any freelancer’s life can ever be – it’s time I returned to the Great Guitarists series, and returned to the Blues. This time, we’re sticking with the Blues to honour one of the greatest slide guitar players in the history of guitar: Bonnie Lynn Raitt…

Born in California in late 1949 to a musical family, Raitt first picked up the guitar at the age of eight and continued learning songs throughout her teens. She gravitated to a slide guitar technique early on, although she still viewed music as a hobby while going to study Social Relations and African Studies at University (that’s college for American readers). Indeed, she planned to work in Africa after graduating, but a road trip to Philadelphia and some early gigs backing Mississippi Fred McDowell started Raitt on the path towards a career in music which has seen her win fifteen Grammy Awards and become one of the very few elder stateswomen of the Blues.

Her eponymous debut album was released in 1971 to critical acclaim at a time when women generally weren’t praised for the guitar playing. Following a tradition set out at the very start of Rock’n’Roll by Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Raitt’s playing earned the respect of her peers, and wider public recognition followed in 1977, with the commercial breakthrough of her sixth studio record, Sweet Forgiveness. Since then, despite periods where she’s taken time out to deal with addition health and personal issues, Raitt has maintained a steady release of records and continues to perform and record to this day.

Slide technique

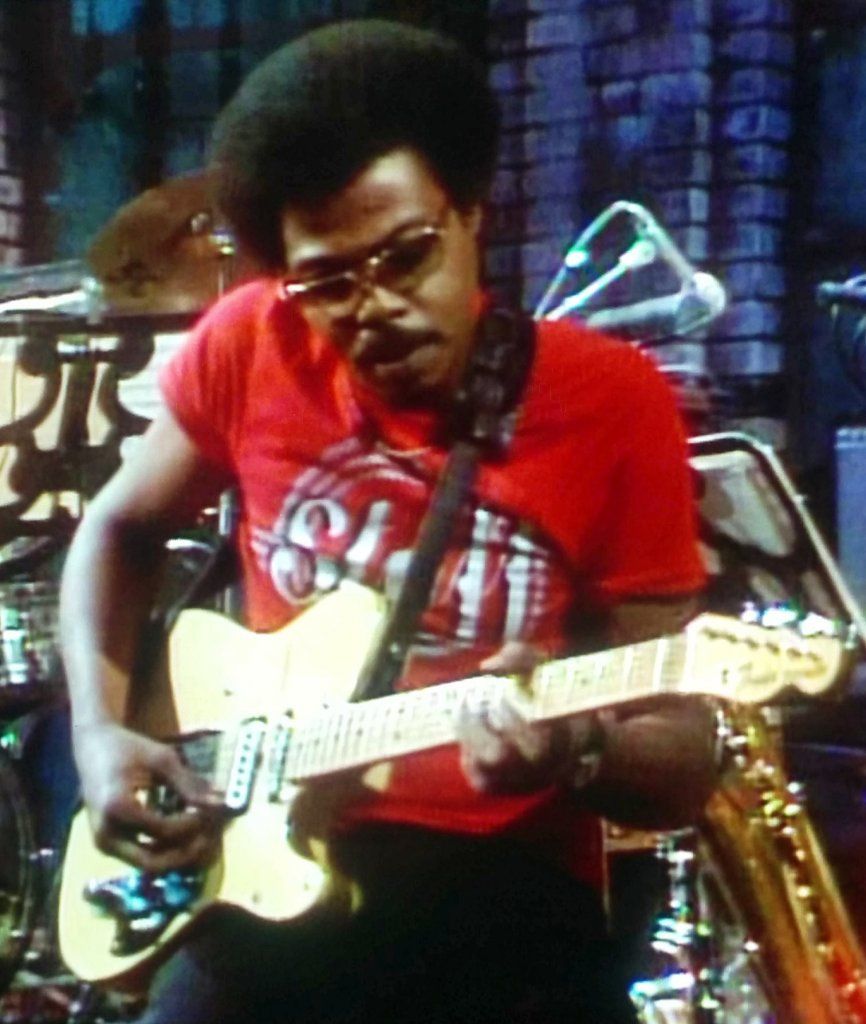

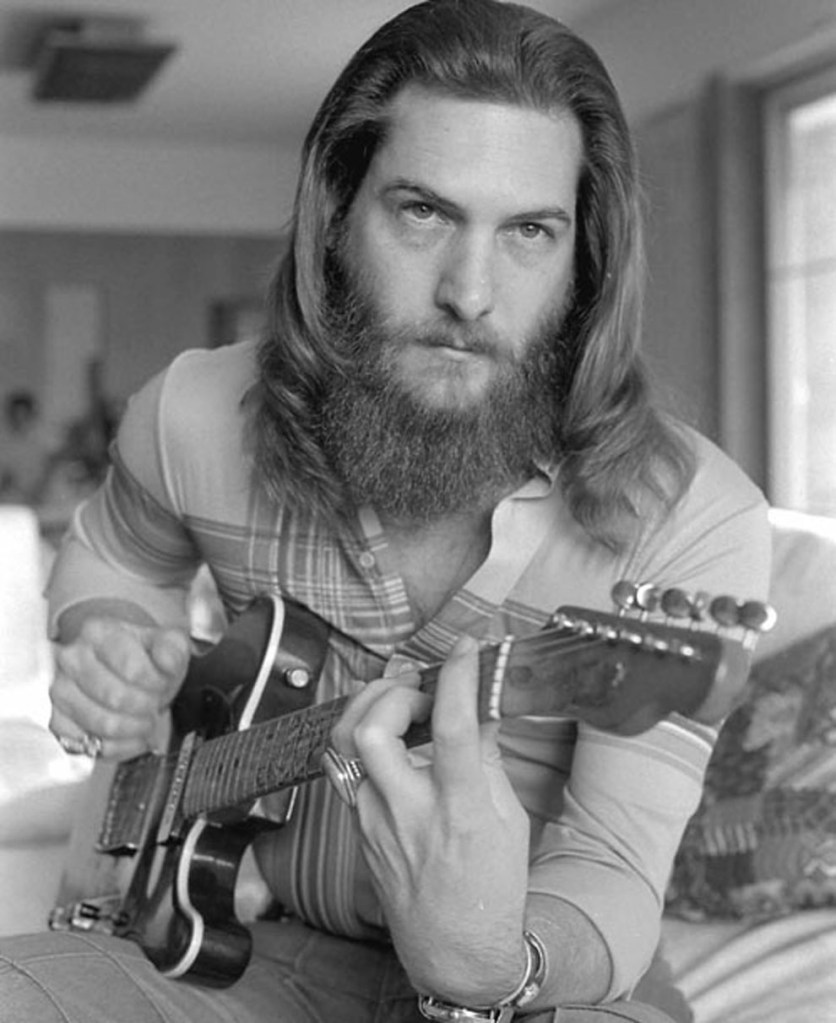

Raitt learned about “bottleneck” playing from old blues records, and started with a glass bottle, inspired by slide legend Duane Allman. She has admitted her technique is a little unorthodox, since she wears her slide in her middle finger, rather than the little or ring fingers, which is far more typical.

However, being able to hold her slide between two stringer fingers gives her an element of control that’s sometimes lacking in the majority of slide players who prefer to wear their slides on their ring or little fingers. Also, Raitt is always precise with her movements during her solos. Although the middle finger is a rare choice, it is something Raitt has in common with Joe Walsh (James Gang, The Eagles) and Billy Gibbons (ZZ Top), which is rather good company for her (and me, another middle finger slide-ist) to be amongst!

Equipment

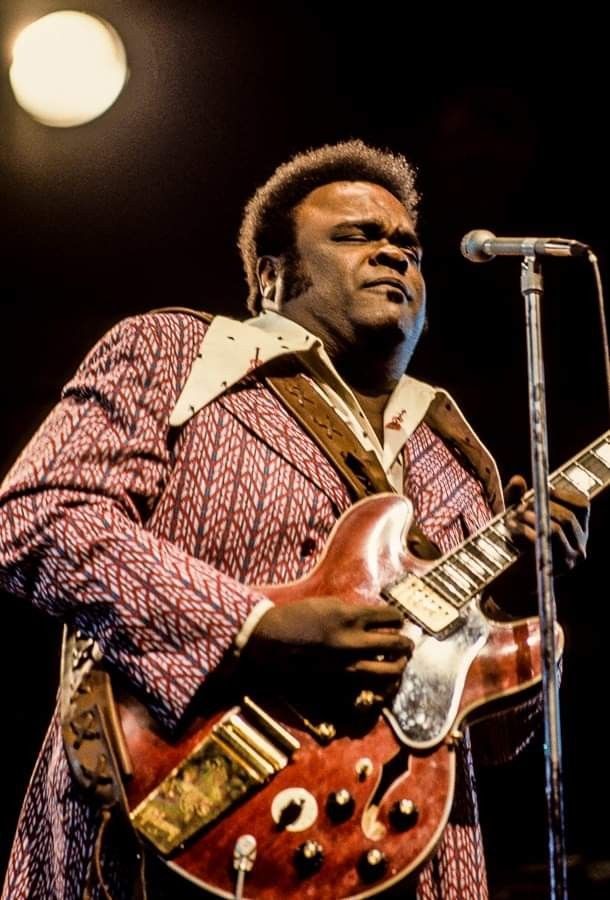

Raitt can be seen in pictures with a variety of guitars, but her most famous tone comes from a Fender Stratocaster she bought in 1969. The single coil pickups help the biting tone of her slide playing to cut through more clearly. She also plays a Gibson E-175 on occasion, and seems to favour Guild acoustic guitars. Amplification can vary, but Raitt appears to use Black Cat combos more often than not on tour, and for added bite, usually has a Rat distortion pedal in her armoury.

Her preferred tuning is Open A (low to high: E, A, E, A, C#, E), which is simply the more common Open G, raised by a whole tone – so if you (like me) often keep a guitar tuned to Open G for slide work (or bashing out Keith Richards style open-tuned riffs), a capo on the 2nd fret saves you having to retune (and intonate) your guitar.

Recommended listening

You have eighteen of Raitt’s studio albums to choose from over her five decade long career, and they each have something to offer in terms of excellent slide guitar tone and a melody-focused soloing approach. As well as previously mentioned successes such as Sweet Forgiveness (1977) her 1971 debut and its follow-up, 1972’s Give It Up, Raitt’s fans rate 1989’s Nick Of Time and Luck Of The Draw (1991) as great showcases of her guitar and vocal talents. Raitt has also appeared as a session musician, performing guitar or backing vocals on records by a range of artists, from Roy Orbison, Aretha Franklin and Bruce Hornsby to Little Feat, The Pointer Sisters, and many more…

It’s also worth highlighting her numerous guest appearances with other Blues greats, from Mississippi Fred McDowell and John Lee Hooker to her fantastic rendition of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Pride and Joy at the tribute concert in his honour (after his tragic death) recorded in Austin, Texas in 1995, alongside BB King, Buddy Guy, Eric Clapton, Dr John and Stevie’s brother Jimmy Vaughan.

Final thoughts

I’ve long admired Raitt, not only for her slide guitar playing, but for her social conscience and lifelong activism, using her voice to speak out about global and environmental issues throughout her career. I also recognise how hard it is to take sabbaticals form the music industry, where the fear of being forgotten, dropped by a record label, and therefore at risk of losing one’s income has driven countless musicians to an early grave. Yet Raitt is on record for speaking about taking time out in the 1980s to properly deal with her alcohol and substance addictions, as well as taking time to properly grieve following family bereavements. This is a good example of taking time for oneself, not just to survive, but to thrive – something too many of us can struggle to do, and indeed be made to feel guilty for.

In this increasingly busy and high-pressured world, perhaps we should all be a bit more like Bonnie Raitt by taking more time to heal when we need it, and keeping our unique voices ringing out about to speak up when it matters – both creatively and socially.

You must be logged in to post a comment.