Loved by some, derided by others. You will have heard at least some of the music of The Doors.

Despite their short time together at their height, they left behind an impressive legacy. As with similar articles (such as my look at the wider impact of The Animals and The Bryds), I’ll try to keep it brief, focusing on the factors that I believe made The Doors unique and influential.

So, on the understanding that this is not a definitive history, let’s dive in…

A quick rise

The Doors were formed in Los Angeles in 1965 by vocalist Jim Morrison and keyboardist Ray Manzarek, initially under the name Rick & The Ravens with Manzarek’s brothers Rick and Jim. They soon changed their name to The Doors in honour of Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception, recording their first one demo along with drummer John Denmore. After brothers Ray and Jim left the group, the group, guitarist Robby Krieger joined the band and the classic lineup of The Doors was complete.

They very quickly became popular, despite having played few gigs. In the start of 1966, the band managed to secure a residency at The London Fog club on Sunset Strip by having all of their friends turn up to their initial trial gig and cheer loudly. This residency not only gave Morrison the chance to overcome his stage fright, but also provided an opportunity for the band to experiment with their songs, many of which appeared on their debut album the following year.

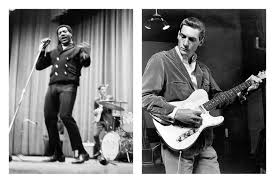

In May 1966, the group became the house band at the more prestigious Whiskey a Go-go club, supporting the visiting acts such as Van Morrison with his band Them. By August, The Doors had been signed to Elektra Records. They recorded their eponymous debut album the same month, released at the very start of 1967. Their follow up, Strange Days, was released in September of the same year. This started an impressive run which saw the band release one studio album every subsequent year, ending with LA Woman in April 1971.

A polarising frontman

Over the years, Morrison’s behaviour had become increasingly erratic and difficult for the ban to manage. He was already living in Paris by the time LA Woman was released, taking time out from the group to focus on his poetry. He was dead just three months later, likely of an accidental overdose on heroin (although no autopsy was performed to officially rule the cause of death).

I put out a poll on my social media pages to canvass for opinions on The Doors. It seemed that, by and large, those who said they didn’t like the group generally cited Morrison’s vocal delivery style lyrics, or his persona as the main reason. He seems to have become a love-him-or-hate-him figure in music history. For some, Morrison represented the epitome of a certain type of masculine sexuality. Several bedrooms have been adorned with posters featuring well-known pictures of Morrison, topless and brooding. which seemingly turned ob as many people as it turned off.

Furthermore, in passing away at such a young age, fans never had the opportunity to watch him grow old, or indeed display an change or sense of ongoing maturity in his work. What is left behind becomes immortalised, while Morrison himself became a legendary figure. His grave in Paris remains a popular tourist attraction for would-be Bohemians to congregate.

But what we’re the critics opinions of Morrison before he died? The music of The Doors left fans divided. Fiona Sturges claimed that “Lester Bangs was right when he described Morrison, the son of a US rear admiral, as ‘a drunken buffoon masquerading as a poet‘” (quoted in The Independent, 2012). Yet Bangs had the maturity in later years to recognise the legacy of Morrison on his peers:

Think about it. Without Jim Morrison no Patti, but what’s more or less no Iggy perhaps no Bryan Ferry in his least petit-bonbonned moments. Without Iggy, of course, no punk rock renaissance at all, which means obviously that Jim was the real father of all that noise

Lester Bangs, writing in Creem Magazine (1981)

Similarly, the music was considered by some to be twee in places (with those fiddly organ lines) or even downright pretentious. Listening to their entire run of six albums highlights inconsistencies in style, but I’d argue that this was common for groups at the time. In a time of psychedelia and increasing experimentation in pop music, record executives seemed to have lost their sense of what would sell and what wouldn’t, and allowed some artists time – and often several albums – to find a formula that worked. The Doors were no exception to this, although I believe they stood out for a few reasons.

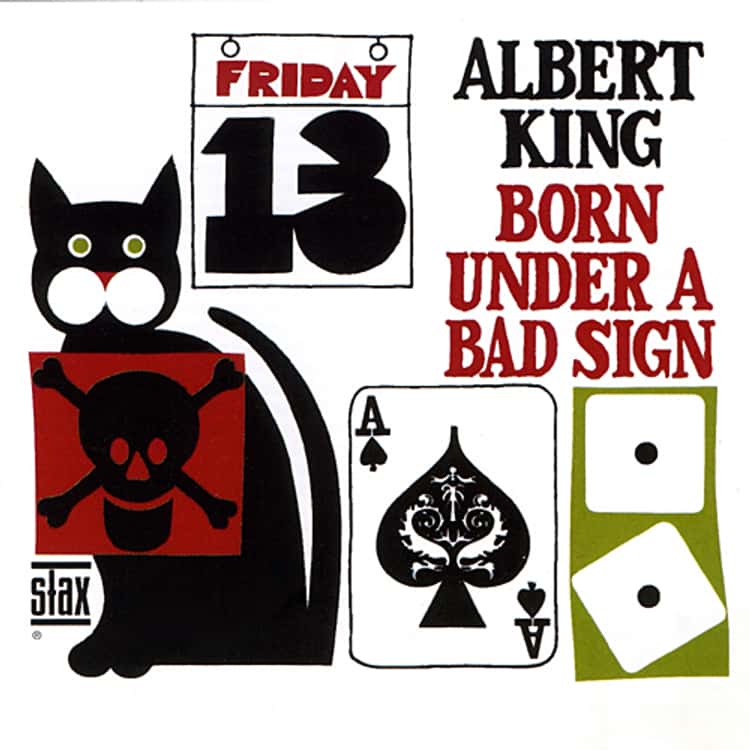

Grounded in the Blues, but not limited to them

Like many bands of the time, The Doors were rooted in the Blues as the bedrock of their sound. When he wanted to, Morrison could write lyrics that were reminiscent of blues men such as Muddy Waters or Howling Wolf,such as on Love Me Two Times or LA Woman, for two well-known examples.

Musically, many of the songs were grounded with blues-based riffs, common to other R&B acts of the time. It was the combination of electric blues with the more poetic elements to Morrison’s words, coupled with a sense of exploration and a willingness to add elements of jazz to their sound, which gave The Doors an edge over their contemporaries in the world of psychedelic rock.

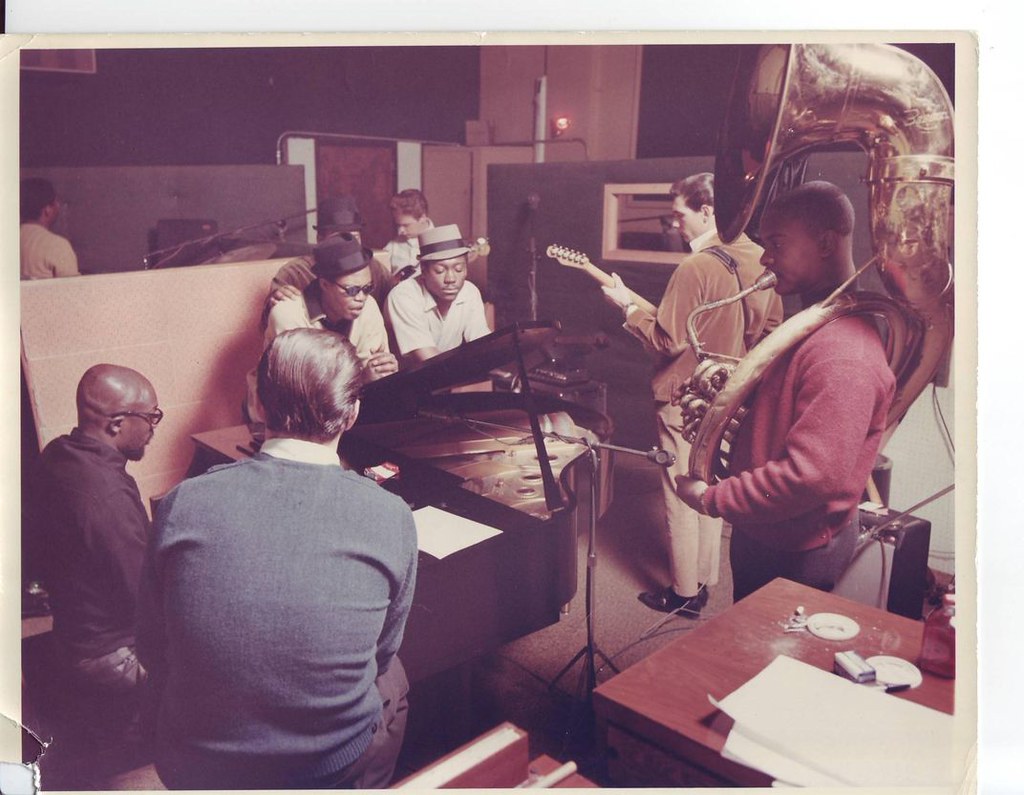

No bass player?

No – not for their live performances, at least.

In the studio, Doors producer [name] felt that Manzarek’s left-hand organ bass notes didn’t cut through as well as the second of a plucked string, and a session bass player was called in. This started something of a tradition for the band, who had bass guitar on the vast majority of their recorded material while maintaining their bass-less quartet format onstage.

In most cases, the session bassists – including bit hitters such as Harvey Brooks (who had played on Dylan’s first electric album and subsequent live shows) and Jerry Scheff (who has played with everyone from The Everley Brothers to Elvis Presley’s Vegas band) – were given strict instructions on what to play. This often following the Blues-based riffs. Otherwise, they simply filled in the sonic space a little, leaving ample room for [keys] and [guitar] to take flight, often in surprisingly intricate ways (a full and fascinating read on the bass players working with The Doors can be found here).

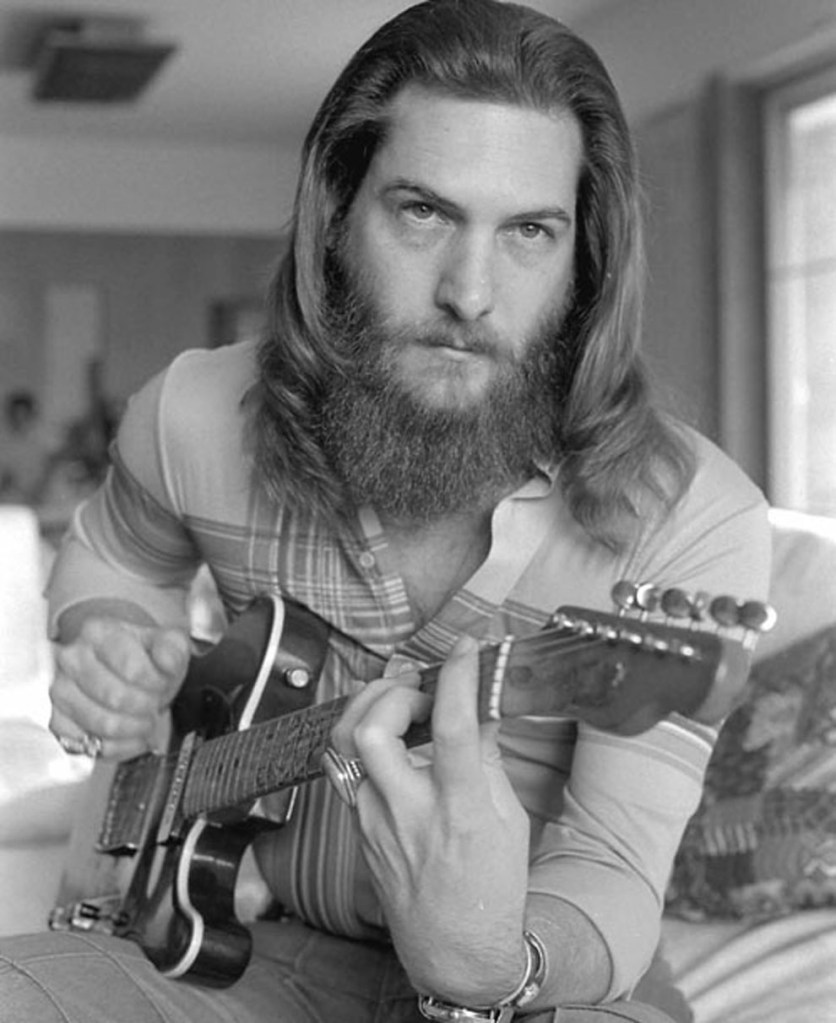

Robby Krieger’s guitar style

The final element to be discussed is The Doors’ guitar player, Robby Krieger. Although the last member to join the band, his playing gave the group a certain ‘lift’, mixing various styles and moving beyond solely blues-based lead lines.

Before picking up the electric guitar, Krieger had studied flamenco, who requires a strong right hand picking technique. Elements of this can be heard throughout the band’s output, not only in overt references such as Spanish Caravan, but also in his jazz-rock solo on Light My Fire. Krieger also maintained the flamenco/classical tradition of playing fingerstyle, eschewing plectrums (is it that plectra?) for his entire career.

As I sat down to research and write this article, I started to realise the extent to which Krieger had been an influence on my own lead guitar playing. However, I rarely cite him as an influence. This may due to our similarities in background; I too, was a classical guitar player long before I started on the electric guitar, and my first electric influences were blues players and the experimental artists of the nineteen-sixties.

It may also be that Krieger’s influence came indirectly, via the first ever tuition book I bought to help me learn lead guitar, Lead Guitar by Harvey Vinson (which is a whole thing in itself – expect an article all about it in the near future). Looking back through the example riffs in that book, most of them could easily have been lifted from Doors tunes. I even owned a cheap SG copy too, but that’s a story for another time…

Recommended listening

There’s something interesting to be found on all six of the band’s studio albums. It is worth giving them all a listen to see what jumps out for yourself. Having said that, I find that for me, their first two LPs The Doors and Strange Days (both 1967), as well as their final offering, LA Woman (1971), showcase the group at their finest.

As always, let me know what you think. I enjoy having discussions with readers who get in touch and would love to know your opinions on The Doors, Morrison’s legacy, Krieger’s technique and everything else. But for now, this is the end…

You must be logged in to post a comment.