I recently bought the TE-69 ‘Hot Rod’, Harley Benton’s version of the Thinline Telecaster, and it has not disappointed…

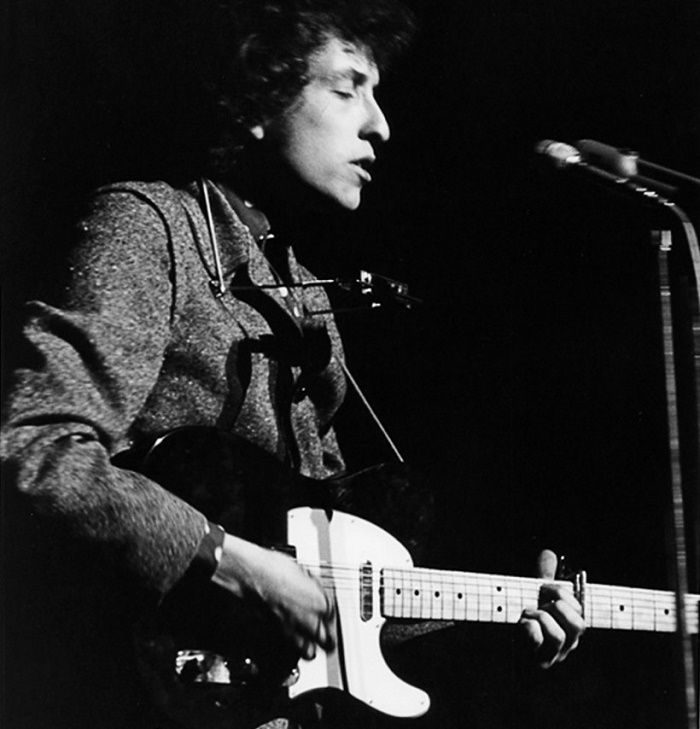

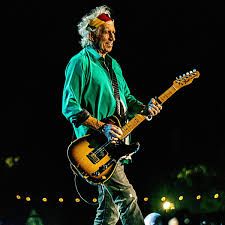

When is a Telecaster not a Telecaster? Is it when a company other than Fender (or Squier) makes one?

That might be true in a legal sense, but the soul of Leo’s original solidbody design lives on in countless iterations and imitations, with a version made by almost electric guitar manufacturer you could think of.

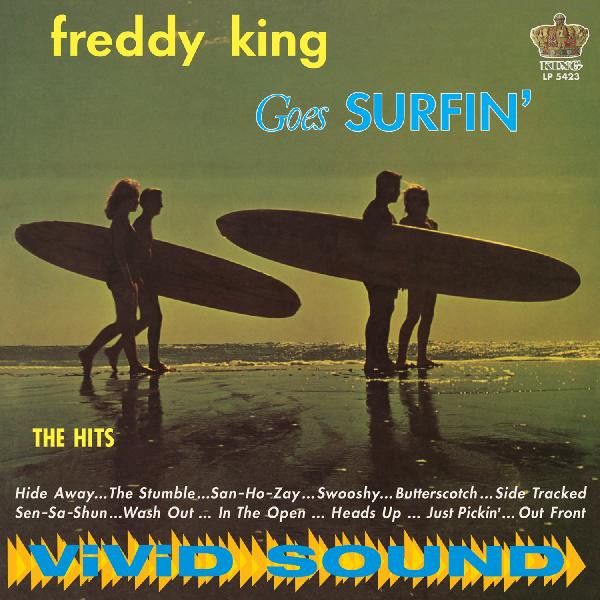

Naturally, German super-giant of musical instruments Thomann have – via their Harley Benton range – their own take on the classic Tele. However, in 2022, they announced a new variation on the theme; a recreation of the Thinline Telecaster.

The Thinline was brought in towards the end of the 1960s in order to accommodate customer feedback about the weight of the guitar (the Tele is well-known as one of the heavier guitars available, even now) by carving cavities into the body, adorned with a violin-style F-hole. The scratchplate was altered to accommodate these changes and while it didn’t catch on hugely the first time around (it was discontinued after a decade), the Thinline has become something of a classic Tele variant. Harley Benton’s version is more affordable than even the Squier Classic Vibe models (Fender’s own in-house and high quality budget range), but is it as good?

What’s in a name?

The full name TE-69TL Hot Rod NT Roasted, while quite the mouthful (I’ll be referring to it as the TE-69 from here on in), indicates the key characteristics of this guitar. TE-69 denotes that it is a 1969-inspired Telecaster model (’69 being the year Fender originally introduced the original Thinline Tele); TL stands for ‘thinline’; Hot Rod refers to the sneaky humbucker in the bridge position (more on this later); finally, NT means it has a natural finish and Roasted refers to the neck and fingerboard being made of roasted Canadian Maple.

Clear? (like the finish)

Good.

Full specifications from Harley Benton:

- Ash body with F-hole

- Bolt-on vintage ‘caramelized’ Canadian maple C-neck with roseacer skunk stripe

- Fretboard: Vintage ‘caramelized’ Canadian maple

- Fretboard radius: 305mm

- Frets: 21

- Scale: 648mm

- 42mm graphite nut

- Double-action trussrod

- Neck pickup: Roswell THE Alnico-5 vintage TE -style singlecoil

- Bridge Pickup: Roswell TEK-B Alnico-5 Stacked Humbucker TE pickup

- 1-volume, 1-tone & 3-way switch

- ‘Deluxe’ chrome hardware

- Kluson-style tuners

- Hi-gloss Natural finish

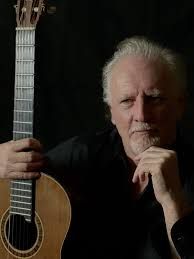

This guitar has received rave reviews since its release, for the great build quality (shared with the rest of their guitars) as well as the sound and feel of the neck. Having previously said I was looking to buy a Telecaster-style guitar, I noticed a friend selling his own TE-69 at the end of last year, so took the plunge.

What’s driving the Hot Rod pickups?

The secret weapon in this particular model is the Bridge Pickup (a TEK-B by Harley Benton’s regular pickup partner, Roswell). While this pup looks like a regular Tele single coil, it is in fact two alnico V single coils stacked on top of each other, giving it a beefier sound and an output of around 10.9k. This output is reduced somewhat in single coil mode (activated by pulling up the tone knob), leaving the sound a little weedy and not like a true single-coil.

The good news is that the humbucking mode isn’t overwhelming and matches well with the neck pickup (a regular single-coil with an output of around 5k). I found the neck to be beautifully clear and the bridge (in the beefier humbucking mode) to sound like an ever-so-slightly hotter version of a great Tele bridge pickup. The only real negative is the bridge being underwhelming in coil-split/single mode. Yet this is often the case with split humbuckers – you almost never get the sound of a regular single-coil. I guess a trade-off has to be made somewhere.

In use

I aim to be clear and honest when writing reviews, and I will mention the few negative aspects of the TE-69 shortly, but frankly, it’s a lovely instrument. This is a solid guitar that sounds exactly like what you hope and expect a Telecaster to sound like, and feels incredibly well put-together. The C-profile neck feels chunky but far from unwieldy in my hands and the 12″ radius still feels very comfortable for chord work.

I have played this axe at a few recent gigs, covering a wide range of styles, from funk & soul to punk, indie and classic rock. It handled everything I threw at it brilliantly. Clean sounds are bright and twangy, and the middle position (both pickups on at the same time) remain one of my favourite guitar tones. Meanwhile, the dirtier, just-breaking-up sounds had a lovely growl to them which cut through the mix onstage without being too sharp. Going heavier still (rare for me) didn’t cause any problems and it handled sounded great playing wild, fuzzed-out psychedelic solos.

Tele’s are famously versatile guitars, and this Tele copy is no exception. I have previously written about the best all-rounder guitar, but that was before I owned a Telecaster. I might need to go back and revise that article now…

Also, like all good Telecasters, it was almost impossible to knock out of tune, even during my more heavy-handed moments. For a guitar that costs less than £200, it’s really hard to find a fault that would make this bad value.

Downsides

I have already mentioned how the bridge pickup feels a little thin (but not without its merits) in single-coil mode. As I said earlier, it’s not a bad sound, but I prefer the humbucking mode, which manages to sound full and full of that classic Tele bite without being overpowering.

I have heard that fret ends can be a little rough on Harley Benton guitars which have come direct from the factory. I can’t comment on the TE-69 specifically, because I purchased mine second hand. I know it had been set up previously, which will have likely included some form of fret-dressing. This isn’t a huge issue, just something to bear in mind when buyung any budget guitar.

The only other real criticism I have of this guitar is that it isn’t really much of a semi-hollow guitar. The original Fender Thinline Tele was built with two large cavities cut into the wings on both sides of the pickup (not unlike a semi-hollow with the pups mounted onto a centre block), making it significantly lighter. However, only a very small part of the body in the TE-69 has been removed; the small section immediately under the F-hole. Apart from this relatively small section, this remains a solid guitar.

As a result, the TE-69 doesn’t really have the sense of ‘airiness’ that I get from my Elderwood (which is effectively a semi-hollow), and it’s a lot heavier (in sound as well as weight) than my Harley Benton HB-35 Plus. But this doesn’t stop the TE-69 from being a great guitar. I’d still recommend it, but be mindful that it’s not really any lighter than an average Telecaster.

What else? Cosmetic preferences mainly. I’m not a fan of the black pickguard, but then I don’t like the original ’69 pearloid either. If I keep this guitar, I’ll almost certainly swap the pickguard for an aged white / mild cream instead, but that’s a decoration issue and doesn’t affect how the guitar plays or sounds in the slightest.

One final, unfortunate thing to consider is that at the time of writing, this guitar no longer appears to be in stock on the Thomann website. Given the quality of this instrument, second hand prices may be higher than the original RRP. The upside to that is the one you buy may already have had a decent set up, as mine had, meaning the usual brand-new-budget guitar issues (such as fret ends) will have already been ironed out.

In Summary

It sounds lowdown and dirty. It weighs a tonne. And I couldn’t put it down.

The TE-69 pays homage to a classic Fender guitar, sounds like a Telecaster, plays like a dream and cost far less than a fancy meal out for two. If you see one come up in the usual second hand places, snap it up and enjoy having a versatile and reliable guitar in your armory.

You must be logged in to post a comment.